INTRODUCTION

The South Asian (SA) population includes diverse individuals originating from India, Bhutan, Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh [

1–

2]. The SA diaspora is a subgroup that migrated to the Caribbean, Africa, Europe, Canada, the Middle East, and other parts of Asia and the Pacific Islands [

1]. In Canada, the South Asian population reached 2.5 million in 2021 and is projected to increase to 5 million by 2041 [

3–

4]. The majority of South Asians reside in Toronto, Ontario, and Vancouver, British Columbia [

5]. This population is disproportionately impacted by chronic diseases compared to their white counterparts (referring to those with European ancestry) [

6–

13], with SA adults having an 8.1 times higher prevalence of developing type 2 diabetes (herein referred to as diabetes) [

8]. The latter exacerbates the prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [

9–

17].

Majority of the literature on SAs attribute the higher rates of diabetes and CVD to biomedical and behavioural risk factors [

18]. Studies report SAs in Canada are more susceptible to diabetes due to their fetal programming [

18], have a higher amount of visceral fat and fatty acids, lower HDL-cholesterol levels, and greater insulin resistance compared to whites [

12,

18]. They also state SAs engage in less physical activity, have a high-caloric, fat diet, and low fibre intake [

12,

18], which is postulated to occur through acculturation in Westernized countries [

19–

20]. Thus, diet and physical activity are often seen as modifiable risk factors for diabetes and CVD [

2,

21–

27]. However, these studies illustrate a white normative and pathologizing perspective on diet when making comparisons to other cultures [

28–

31]. This ignores the broader societal context and creates a discordance with nutrition recommendations in Canada [

28,

32]. The individualistic focus disregards how chronic disease is influenced by the social determinants of health (SDH); the interplay of social, economic, and cultural aspects that affect an individual’s or population’s health status, which creates a circumstantial disadvantage for certain groups [

33–

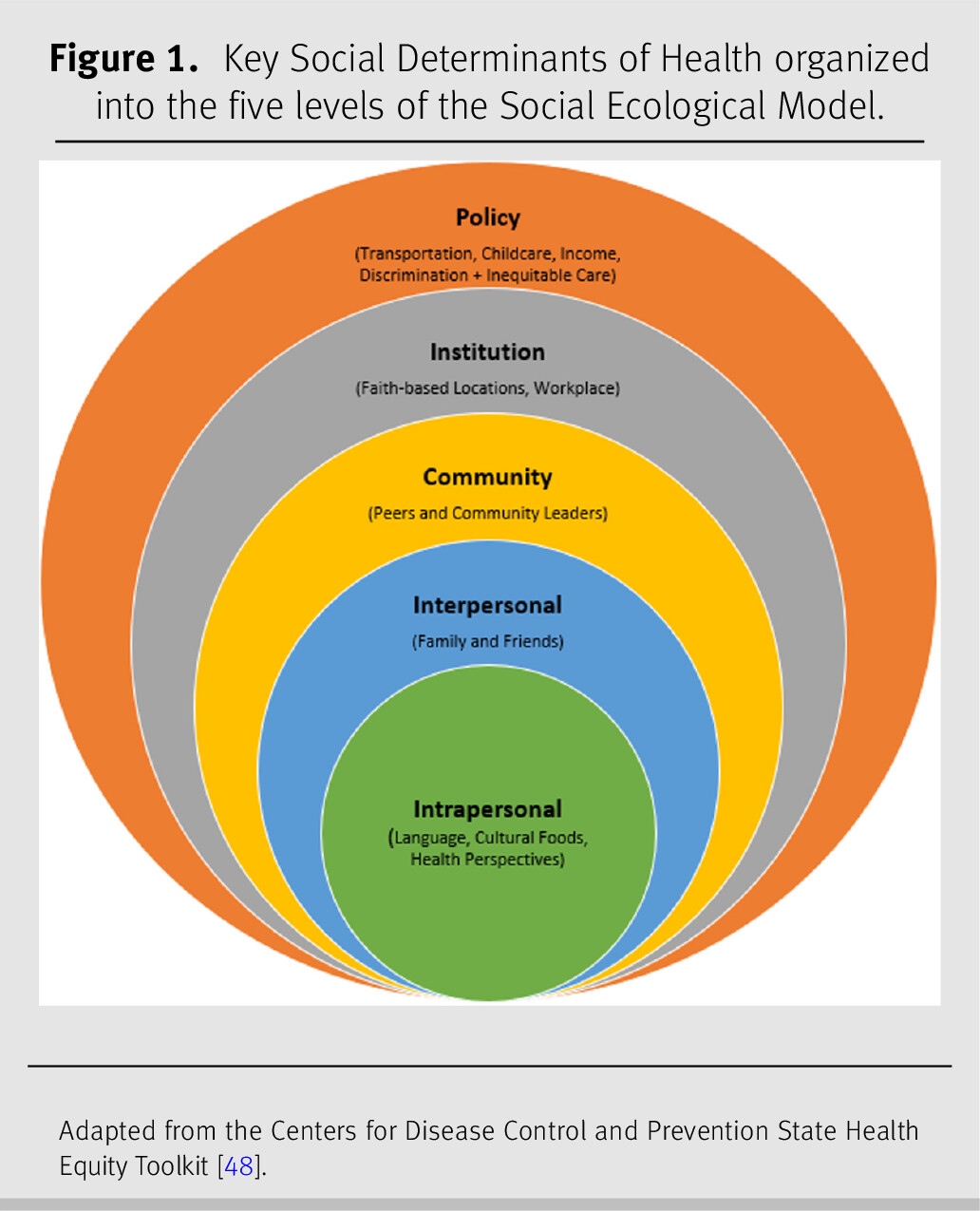

37]. Current research suggests that the Social Ecological Model (SEM) is commonly utilized to map SDH (

Figure 1). This model serves as a guiding framework to determine the causes of public health nutrition issues and to propose strategies for change [

38–

41,

46]. A key SDH for SAs and their chronic disease risk is racism [

15,

35–

37,

42]. SAs and other ethno-racial groups are met with white normativity in societal structures, including in nutrition care [

28,

31,

35,

47].

There is limited literature supporting the influence of the SDH in nutrition care interventions for SAs, which ignores health inequities in this population. The aim of this narrative review [

43–

45] was to explore SDH in nutrition care interventions for diabetes and CVD in the SA diaspora residing in Canada, and to propose equity-informed recommendations for dietitians working with this population.

METHODS

Search strategy

For this narrative review, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and Scopus databases were searched in November 2021, using the following keywords: “nutrition education”, “nutrition counsel*”, “nutrition intervention*”, “family care”, “peer program”, “Bangladesh”, “India”, “Nepal”, “Pakistan”, “Sri Lanka”, “Bhutan”, “South Asia”, “Canada”, “culturally sensitive”, “culturally appropriate”, and “cultural safety”. Selection criteria included peer-reviewed journal articles that focused on SA adults residing in Canada with ancestral origins from Nepal, Bhutan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, or Sri Lanka, and nutrition interventions for SAs with type 2 diabetes and/or CVD. Articles were excluded if they included SAs residing outside of Canada or SAs with type 1 diabetes; if they were conferences or poster abstracts, letters, commentaries, editorials, and presentations; written in a language other than English; and were published before the year 2000 (previous 20 years to reflect the increase in diversity of SAs in Canada).

Data collection and synthesis

Two authors (SB and CB) screened articles by title and abstract. Descriptive phenomenology was used to chart key study information for studies meeting the eligibility criteria. The analysts (SB and CB) applied thematic analysis to independently identify relevant SDH in the articles and grouped them into the five SEM levels (

Figure 1) [

41,

46–

48]. Analysts then compared their categorization, and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

DISCUSSION

This is the first narrative review to utilize the SEM as a guiding framework to highlight the role of the SDH in nutrition care for SAs with diabetes and CVD in Canada. The SEM can encourage dietitians to address the SDH in their practice [

33–

34,

38]. The following SDH were identified in this review: language, cultural foods, health perspectives, family and friends, peers and community leaders, faith-based locations and workplaces, transportation, childcare, income, and, discrimination and inequitable care.

Studies in other countries on SAs have also demonstrated the SDH found in this review. A systematic review identified native language use, culturally specific resources, and family involvement as primary SDH for diabetes management [

64]. As well, dietary changes for CVD management in SAs were difficult to maintain unless there was family support [

67]. SAs perceived advice from peers as familiar and meaningful, while advice from clinicians was unfamiliar and devoid of cultural meaning [

68–

69]. Another study identified that dietary interventions to prevent diabetes in SAs, tend to be extrapolated from evidence found from non-SAs, and align with guidelines not developed for them [

70]. Evidently, the need for co-created community-level interventions for SAs spans across different countries [

64,

67–

70].

Furthermore, workplaces were identified as a barrier for dietary change as many SAs report struggling financially [

51,

61]. SA taxi drivers stated that financially supporting their families was a priority when deciding between attending a healthcare appointment and working; causing them to decide between health or earning an income [

71]. This reflects the systemic issue of working a lower-wage and precarious job that lacks both work flexibility and income security [

72–

73]. The intersection between nutrition care and income is also evident through the prevalence of food insecurity (FI) [

72–

73]. Although only a few studies in this review discussed FI [

53,

65], the prevalence of FI among SAs is high [

18,

72,

74]. SAs account for 15.7% of FI households in Canada compared to 13.2% for white households [

72]. Racialized and low-income groups are more likely to experience FI [

72–

75], resulting in poorer health [

75–

76], and a higher risk for diabetes and CVD-related complications [

72,

77–

81]. A study discussed service provider perspectives on two SDH, employment and income, for diabetes management in SAs [

82]. It emphasized that racism impacts access to equitable employment, which further perpetuates income insecurity for SAs [

83]. Racialized income inequality, along with structural barriers to education attainment, contribute to the experience of FI for SAs [

68,

80–

84]. A multi-level policy approach targeting systemic racism in education and employment can ultimately improve the health of the SA diaspora in Canada [

72,

82].

Culture was an underlying theme in this review, as every culture has food-related values and beliefs [

18,

88]. SAs value community and the need to preserve culture through traditional foods [

18]. This ties directly into their well-being and how they interpret nutrition advice from healthcare providers [

18]. The SDH in this review highlights the current status of Canadian dietitians’ cultural awareness, sensitivity, and competence when working with SAs. Providing culturally appropriate care encompasses awareness, acknowledgement, recognition, and respect around the differences between and within cultures [

89]. Cultural competence focuses on the practitioners’ attainment of skills, knowledge, and attitudes to work respectfully with all cultural groups [

89]. However, dietitians must foster cultural humility and safety to provide inclusive and equitable care to SAs [

89]. Cultural humility is a lifelong process of self-reflection and accountability, allowing clinicians to acknowledge their biases, stereotypes, and prejudices [

89]. Cultural safety takes a strength-based approach to culture in care; it considers the social, political, and historical context of care, and requires clinicians to practice cultural humility; and is only determined by the individual and their community [

89].

Limitations

This review excluded SAs that originated from countries outside of SA, such as the Caribbean or Africa, as they may be considered a subgroup of the SA diaspora [

1]. As well, SAs are discussed as a homogenous group in order to develop a general discourse [

90] on SDH for nutrition care in this diaspora. However, it is important to recognize the diversity within SA communities, including differences in migration histories [

90] and varying definitions of “healthy eating” [

63,

91]. Future research should focus on discovering community-specific SDH for nutrition care.

Moreover, SAs in hospital settings were excluded, as dietary recommendations vary significantly between inpatient and outpatient care. Also, this review did not group findings based on immigrant status, which is a SDH that affects one’s ability to navigate a new environment [

92–

94]. Further investigation should explore this SDH in nutrition care for SAs.

Furthermore, this is not a systematic review, and therefore may lack the comprehensive and systematic nature of searching in all available databases, and did not include an assessment of study quality and certainty of the evidence. Nevertheless, narrative reviews provide a more focused understanding on a specific topic [

45]. Lastly, the majority of literature found focuses on health behaviour change and disregards systemic inequities, such as classism and racism. Further research should assess these facets to highlight their pivotal role in nutrition care.

Recommendations

The following are equity-informed recommendations for dietitians working with SAs in Canada.

•

Include family in client sessions [

51–

52,

58–

59,

61], create collaborative, community-driven nutrition interventions [

94–

95] (e.g., through informal peer counseling, peer groups, or designated community leaders) [

49,

58,

60–

62] and utilize faith-based locations as community hubs for disseminating education [

53,

59,

61–

62].

•

Apply Critical Consciousness Raising (CCR) [

96] theory to increase SA clients’ awareness of SDH that impact diabetes and CVD, empowering them to improve and maintain health [

97–

98].

•

Decolonize diets by countering Whiteness as the norm [

29–

33]. Accommodate language preferences, and incorporate cultural foods and health perspectives into dietary recommendations, as appropriate [

49–

51].

•

Adapt dietary recommendations based on FI status, and mitigate this issue by accommodating client schedules, ensuring services are accessible by public transportation or providing virtual services, as appropriate [

50–

51,

53,

61,

65–

66].

•

Apply an anti-racist lens; a key facet when providing culturally safe care while addressing one’s own internalized racism [

42,

65]. Advocate for policy responses that address FI for racialized groups [

99].

•

Participate in ongoing training on cultural humility and safety, and this requires applying a trauma-informed approach [

89,

100]. Consider the varied migration histories of SAs and the intergenerational trauma that persists [

89,

101].

RELEVANCE TO PRACTICE

As Registered Dietitians, the SDH identified in this review present avenues for improving nutrition care for SAs with diabetes and CVD in Canada. These SDH reflect dietitians’ current cultural awareness, sensitivity, and competence when working with this population. However, the SEM as a guiding framework has highlighted that dietitians should focus on the SDH and implement strategies that consider cultural humility and safety. These equity-informed recommendations are a starting point for dietitians to improve their practice. As the SA population increases in Canada, dietitians must be prepared to utilize their clients’ strengths to provide the highest level of care.

Source(s) of financial support

There are no funding partners for this project, and none of the organizations had any role in the project design, analyses, interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript.