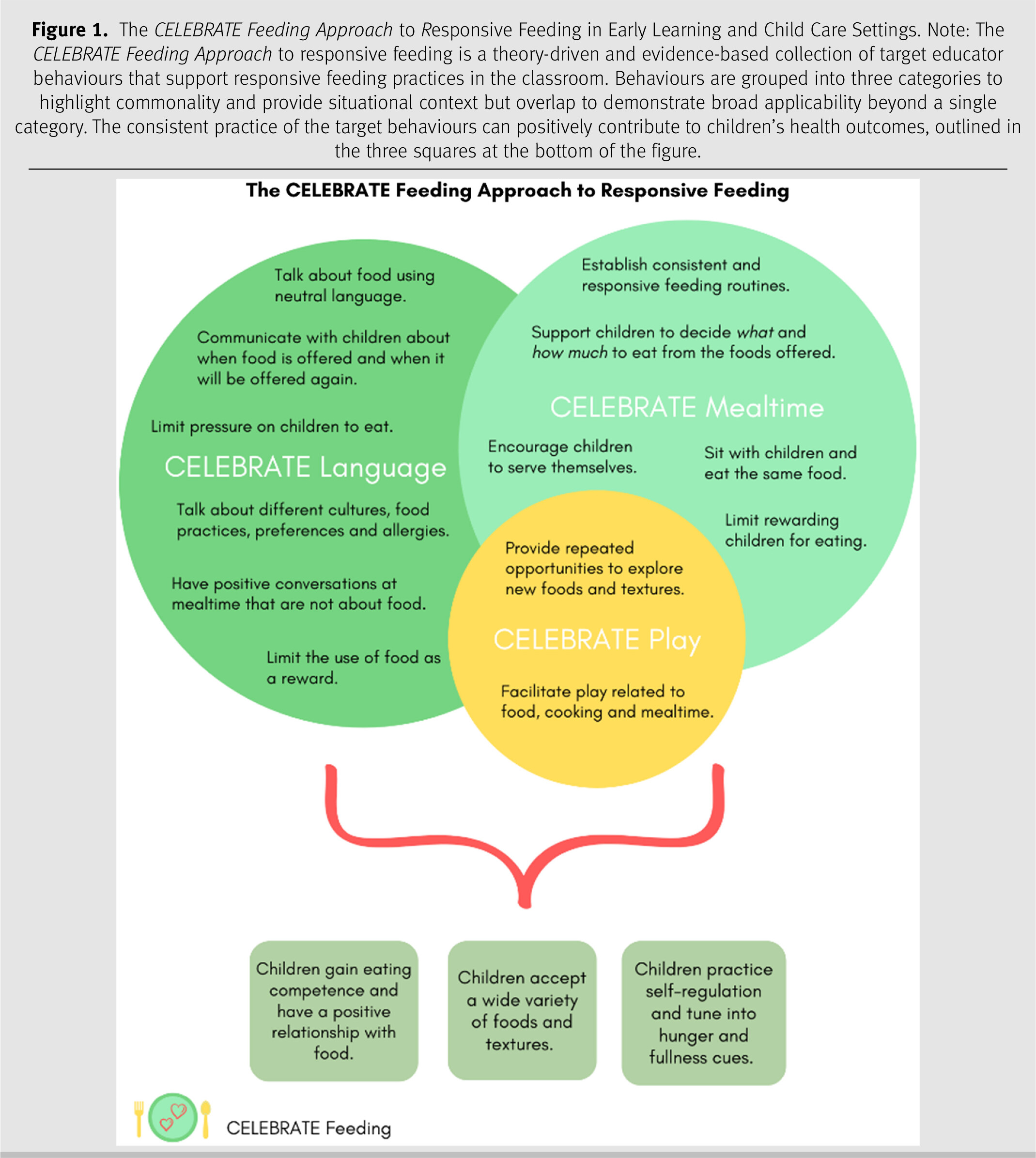

An adequate, varied, and nutrient-rich dietary intake influences the growth and development of young children and can contribute to a decreased risk of chronic disease [

1,

2]. However, when considering the overall health and well-being of children, focusing on intake alone does not adequately capture the impacts of food, feeding, and nutrition [

1–

5]. Responsive feeding practices contribute to children’s health outcomes through the validation of their internal hunger and satiety cues and their capacity to self-regulate energy intake [

6,

7]. Responsive feeding aims to strengthen the child’s self-efficacy, self-regulation, and emotional management throughout early development [

7–

10]. Yet, responsive feeding can have different interpretations in the literature and the concepts that contribute to responsive feeding are varied [

8,

11–

15]. Originally rooted in active feeding [

16,

17] and responsive parenting [

8,

18], responsive feeding has been described as a reciprocal relationship between a child and their caregiver; it is often characterized by the child communicating feelings of hunger or satiety, followed by an appropriate response (or behaviour) from the caregiver [

8,

19].

Early learning and child care (ELCC) settings play an important role in shaping the overall feeding environment for young children. Regulated child care programmes in Canada follow nutrition standards that dictate food provisions [

20,

21], with many also including responsive feeding practices around mealtime to promote a healthy relationship with food (e.g., predictable meal routines, family-style meal service, and caregiver engagement) [

22,

23]. In the short term, responsive feeding helps to support the development of a positive eating experience through the understanding and recognition of internal hunger and satiety cues, the cultivation of skills required for optimal self-regulation and self-control of food intake, as well as emotional regulation related to food and feeding [

3,

7,

10,

24,

25]. Responsive feeding also aligns with increased emphasis among ELCC curriculum frameworks on children as capable and curious, and the role of reflective practice among early childhood educators to value the cultural and social contexts of children [

26]. While there is a current emphasis on responsivity in relation to early childhood education, caregivers who lack confidence in children’s ability to appropriately regulate their own intake, or those who feel stressed about mealtimes, may unknowingly engage in feeding practices that are less responsive [

8,

27,

28]. Practices such as using food to encourage behaviour, using food as a reward, or pressuring a child to eat a certain amount or type of food are considered less responsive and less desirable practices. These behaviours have shown limited evidence of short-term effectiveness and have the potential for creating an unhealthy association with food, as well as the possibility to interfere with emotional regulation and under-or-over consumption [

7,

10,

19,

29–

35].