INTRODUCTION

Personalized nutrition (refer to Supplement A for a list of key terms and definitions) has been presented as “the most powerful antidote to chronic disease” [

1]. In addition, registered dietitians (RDs) and other healthcare providers (HCPs), or non-RDs, perceive that personalized nutrition is “very important” within the field of nutrition [

2].

Nutritional genomics (defined in Supplement A

1), a key component of personalized nutrition, explores interactions between genetic variation, dietary intake, and subsequent health outcomes [

3]. In Canada, regulatory bodies confirm that nutritional genomics is a component of dietetic practice [

4,

5]. Consumers also view RDs as the best providers of nutrigenetic information and advice [

6]. Additionally, the general public has expressed a substantial interest in personalized nutrition based on genetics [

6,

7]. For instance, a Canadian study conducted in Quebec found that approximately 1 in 10 RDs had discussed nutritional genomics with their patients [

8].

As rigorously trained and regulated HCPs, RDs are the most qualified nutrition care providers in Canada, but other HCPs also offer nutrition counselling and

nutrigenetic tests (Supplement A) to patients. Concerns have been raised related to nutrition information communicated by unregulated nutrition care providers, including nutrigenetic information, and related to regulated HCPs such as medical doctors receiving insufficient nutrition education despite their extensive training [

9–

11]. Therefore, it is pertinent to understand the nutritional genomics education and training needs not only of RDs but also of other, non-RD nutrition care providers.

Despite the expectation that RDs and other HCPs play a key role in leading the incorporation of genetic information into nutrition care, research has consistently demonstrated that many lack knowledge, training, confidence, and competence in this field [

2,

12–

19]. Nutritional genomics education is limited in undergraduate and graduate nutrition curriculum, and the quality and evidence-based nature of available training courses are variable [

20,

21]. In addition, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ current recommendations for dietitians wishing to develop expertise in nutritional genomics are quite broad and include elements such as staying on top of high-quality research in nutritional genomics and thinking critically about whether and how genetic testing should be translated into personalized interventions [

22]. However, summarizing and grading scientific evidence are highly complex and time-consuming, and busy clinicians are unlikely to have the time and/or expertise to undertake such a task [

23]. Systematic reviews and clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) would be useful to address this issue but are lacking in the field of nutritional genomics.

Studies have yet to thoroughly assess the experiences of nutrition care providers with nutritional genomics, and their

specific educational and training needs [

12–

17,

24]. Therefore, we sought to fill this gap. The objective of this study was to explore the reasons why nutrition care providers do or do not choose to integrate nutrigenetic testing into their practice and to assess the nutritional genomics training and education needs of nutrition care providers in Canada, while comparing the needs of RDs to those of non-RDs. The ultimate goal was to help guide evidence-based practice in nutritional genomics for RDs and non-RDs who are encountering or incorporating nutrigenetic testing in their practice by providing specific guidance for the development of evidence-based nutritional genomics training and educational materials.

RESULTS

In total, 509 participants started the survey, resulting in a sample size of 457 participants who met the inclusion criteria and continued the survey. Response rates varied by questions; the specific sample size is indicated in the tables, figures, and text. Eighty-one respondents indicated that they had offered nutrigenetic testing to patients in their clinical practice either currently or in the past (17.9%); 372 respondents had never offered nutrigenetic testing to patients (82.1%) (missing data

n = 4). The reasons why participants have or have not integrated nutrigenetic testing into their clinical practice are detailed in

Table 1. Of the 81 respondents with clinical experience in nutrigenetics, 43 were RDs (53.1%) and 37 were non-RDs (45.7%) (missing data

n = 1). Of the 372 respondents with no clinical experience in nutrigenetics, 327 were RDs (87.9%) and 31 were non-RDs (8.3%) (missing data

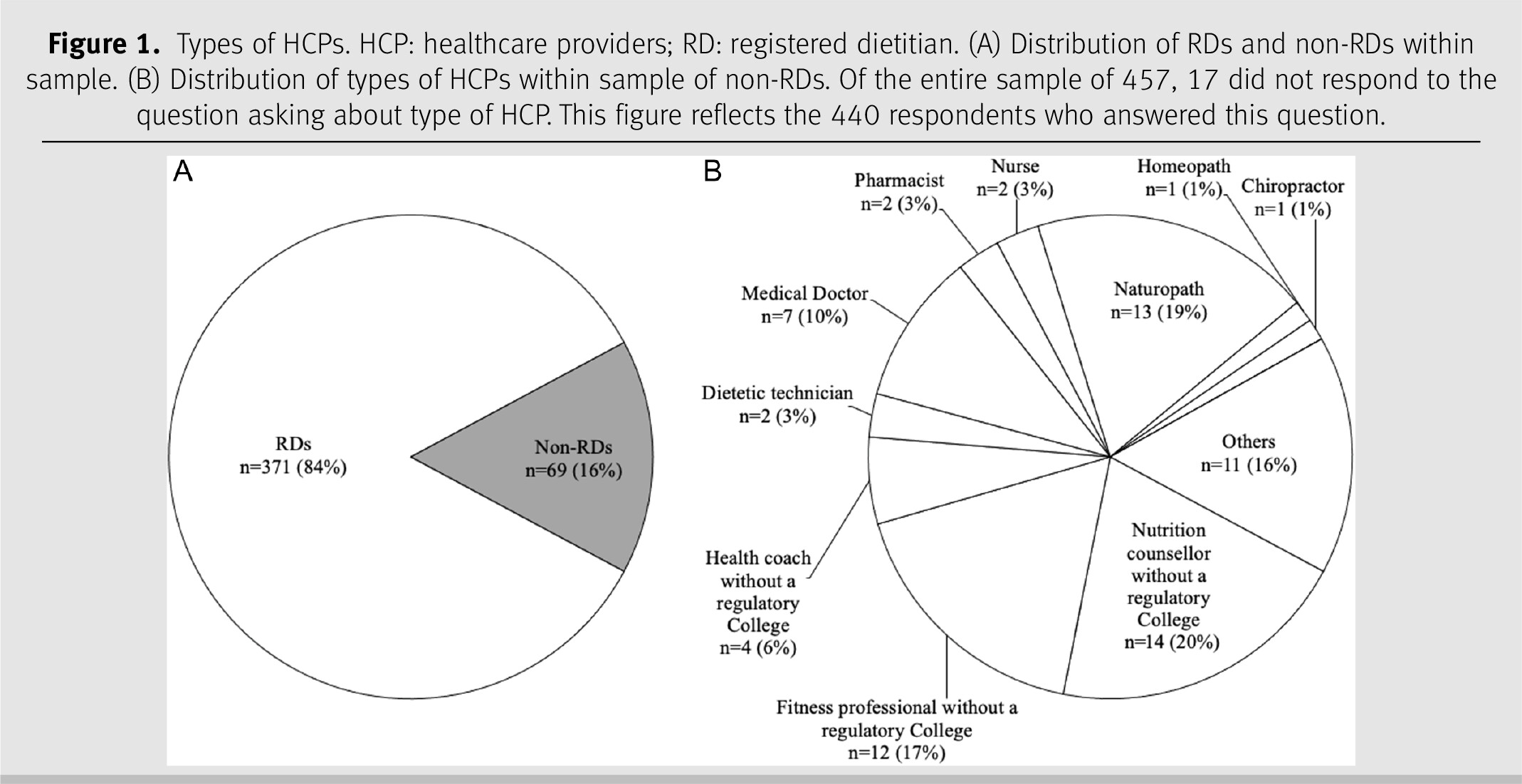

n = 14). The types of HCPs among respondents are shown in

Figure 1.

The level of education and training of the respondents in nutrition and nutrigenetics is depicted in

Table 2. Overall, RDs had significantly higher levels of nutrition education than non-RDs (

p < 0.001), with the exception of a significantly higher number of non-RD respondents with a doctorate degree (

n = 4) compared to RDs (

n = 2) (

p < 0.001). In addition, significantly fewer RDs than non-RDs reported their primary source of nutritional genomics training/education as a college diploma (

p = 0.007) and a master’s degree (

p = 0.026). A total of 230 (50.3%) respondents had no training/education in nutritional genomics. Among the non-RDs with nutritional genomics training, most had obtained training/education through the nutrigenetic company who supplied the tests they sell to clients/patients. This was significantly less common in the RD group than in the non-RD group (

p < 0.001). The qualitative analysis themes for participants responding “other” included obtaining additional nutritional genomics training/education from

colleagues, university courses, and

conferences.

The top three reasons why respondents reported integrating nutrigenetics into their clinical practice were (

i) the perception that clients will be more motivated to change their diet with advice based on their genetics (70.4%;

n = 57/81), (

ii) the perception that their clients are interested in nutritional genomics/personalized nutrition (66.7%;

n = 54/81), and (

iii) the perception that their clients will have better health outcomes (58.0%;

n = 47/81) (see

Table 1). The qualitative analysis when participants selected “other” revealed the theme of

perceived value to the patient. Furthermore, the main reason given by respondents for not implementing nutritional genomics in their clinical practice was (

i) the belief that the implementation process is too complicated (84.1%;

n = 313/372), (

ii) the second most common reason given was that the respondent’s employer does not allow it (77.7%;

n = 289/372), and (

iii) while the third most popular response was the respondent’s personal lack of knowledge and understanding of nutritional genomics (64.2%;

n = 239/372). In addition, key themes in the responses written under the “other” option included

lack of relevance to their field of work, permission, lack of resources, and

ethical considerations.

The topics considered most “useful” in the pooled sample included the practical application of nutritional genomics, its scientific validity, and its impact on health outcomes and dietary change. In this context, scientific validity refers to the quality and quantity of existing scientific evidence for a gene–diet association [

26]. There were also significant differences between RDs and non-RDs in the perceived usefulness of these and other topics; for example, RDs were more likely (80.1%;

n = 293/366) than non-RDs (62.5%;

n = 40/64) to indicate that it would be beneficial to understand scientific validity in nutritional genomics (

p = 0.002) (refer to

Table 2). The

applicability of nutritional genomics to specific areas of nutritional practice was a common theme in the open-ended responses regarding other priority training topics. In terms of most useful resources, significantly more RDs (91.5%;

n = 332/363) perceived CPGs as a valuable resource compared to non-RDs (50.5%;

n = 32/63;

p < 0.001). In addition, a significantly greater proportion of RDs (RDs: 63.4%;

n = 230/363 vs. non-RDs: 38.1%;

n = 24/63;

p < 0.001) perceived the value of position statements from regulatory bodies and nutrition organizations, as well as accredited comprehensive online courses compared to non-RDs (RDs: 65.6%;

n = 238/363 vs. non-RDs: 55.6%;

n = 35/63;

p = 0.025). For those who selected “other,” the common theme identified was

disease-specific guidelines. The topics deemed by RDs as priorities for future CPGs development were personalized nutrition for cardiometabolic disease prevention/management, followed by personalized nutrition for cancer prevention, and finally, macronutrients and their impact on body composition (see Supplementary Figure 2b). The lowest priority topics for RDs were genetically determined taste preferences and their impact on food/beverage intake, personalized nutrition for sports performance, and personalized nutrition for rare genetic diseases. In contrast, the highest priority for non-RDs was personalized nutrition for inflammation, followed by macronutrients and their impact on body composition, and micronutrient absorption/metabolism. Other priority topics for CPGs submitted by respondents in open-ended written responses were

psychological/mental health, gastrointestinal health, and

bone health.DISCUSSION

This study assessed the educational needs and experiences of RDs and non-RD nutrition care providers in the field of nutritional genomics and evaluated differences between these two types of HCPs. It was observed that these HCPs are choosing to integrate nutritional genomics into their practice primarily because they perceive it is beneficial for their clients in a variety of ways. For example, respondents perceived that nutrigenetic testing could help motivate patients’ nutrition-related behaviour change, which is also supported by the findings of the most current systematic review of randomized controlled trials on this topic [

27]. Client requests for genetic testing were also among the main reasons for implementation, reflecting the growing demand for personalized nutrition in Canada [

6,

7,

28,

29]. Nutrigenetic testing has been available in Canada for over a decade while sales have grown significantly since 2016 [

30]. A recent analysis found that there are eight companies that offer nutrigenetic testing services to Canadians [

9]; however, the market is constantly changing with some companies shutting down, and some new tests becoming available. Costs of these tests vary from $90 to $450 CAD depending on the provider [

9]. While some provincial health plans cover genetic testing when a patient meets a pre-specified criteria, coverage remains limited. Instead, consumers typically pay out of pocket. This may explain why 29.8% of respondents reported they had not implemented nutrigenetic testing into their practice due to cost concerns.

Interestingly, respondents who did not integrate nutrigenetic testing into clinical practice indicated that they had not done so, because they considered the nutrigenetic testing process to be complicated. The process of nutrigenetic testing has recently been summarized elsewhere [

9]. Manufacturers of nutrigenetic tests either sell them directly to the consumer or to HCPs who then sell them to their clients. In both cases, once the consumer has sent in their samples (typically from saliva or buccal swabs) to the nutrigenetic manufacturer, it is sent to a laboratory for DNA analysis. The results are either sent to the consumer for self-interpretation (along with supplementary information) or to their HCP. As such, the logistics of conducting nutrigenetic testing in clinical practice requires relatively little of the practitioner. They only need to collect a saliva or buccal cell sample from the client (if the company does not send the test kit directly to the patient/client). It is possible that the part of the process that is perceived as complicated is the interpretation of such results and their application in practice, which has been further detailed elsewhere [

31]. Perhaps more complicated than the actual process of completing nutrigenetic testing in practice is obtaining the required knowledge of nutritional genomics to competently support clients to make dietary changes based on their results. Future research should explore this further, as the present study did not ask for elaboration on the exact component of the process that respondents perceived as complicated. Knowledge has proven to be a barrier for many, considering that a large proportion of respondents also claimed that the reason for not integrating nutritional genomics into clinical practice was a general lack of understanding of the topic. This is consistent with the current available literature that reports that RDs lack confidence and competency in nutritional genomics, which indicates a need for additional training and educational opportunities [

2,

12–

18,

19]. This lack of education is persistent in both Canada and other countries, where the implementation of nutrigenetic testing is also relatively new and thus highly variable [

12,

14]. In Canada however, several colleges such as the College of Dietitians of Alberta and the College of Dietitians of Ontario to name a few, along with Dietitians of Canada, have released statements in support of nutritional genomics falling within the scope of practice of RDs [

4,

9,

32,

33]. It should be noted that while one of the purposes was to explore facilitators and barriers towards nutrigenetic testing implementation, recommending for or against the use of nutrigenetic testing in practice is beyond the scope of this work. In addition, a large percentage of respondents (78%) reported that they had not implemented nutrigenetic testing in their practice because their employer did not allow it, while many were unaware of the existence of such tests or that they could offer such services. Improving our understanding of these perceived barriers would be a worthy topic for future research. In the meantime, the provision of educational resources could help raise awareness of this area of nutritional care among HCPs, as some respondents (

n = 21) did not understand the significance of nutrigenetic testing.

In addition, low levels of formal nutrition education among non-RDs offering medical nutrition therapy (MNT) services are concerning. Dietitians must undergo rigorous training and are mandated and overseen by a regulatory body to ensure ethical and evidence-based practice, while other unregulated nutrition providers are not [

34]. Our study found that the most commonly reported highest level of education for non-RDs was a certificate in nutrition from a private company. The development of educational resources in nutritional genomics must be designed with these varying levels of education in mind. Similarly, significantly more RDs than non-RDs perceived CPGs and position papers from regulatory bodies and nutrition organizations as valuable resources on nutritional genomics. Given that evidence-based decision-making is a required component of dietetic practice, it is not surprising that RDs perceived scientific validity as an important educational topic. In an effort to promote evidence-based practice for all nutrition providers, we must develop education/training resources that reach both RDs and non-RDs since presently both groups are permitted to practice MNT in Canada, including offering nutrigenetic testing [

34]. A lack of evidence-based practice among non-RDs has recently been demonstrated in a study showing that unregulated, non-RDs are providing misleading and potentially harmful nutritional information to Canadians [

35].

As nutrigenetics is already part of the clinical practice of some HCPs, there is an urgent need to develop CPGs so that clinicians can easily identify evidence-based gene–diet interactions. To our knowledge, there is only one existing CPG in nutritional genomics, related to genetically determined responsiveness to dietary omega-3 for alterations in lipids/lipoproteins [

36]. Furthermore, there are only two systematic reviews with evidence grading in nutritional genomics (i.e. summarizing scientific validity) [

36,

37]. One of these reviews was used to guide the abovementioned omega-3 CPGs and identified two nutrigenetic associations with strong evidence, both related to genetic variation, omega-3 intake, and plasma triglyceride responsiveness [

36]. Given that conducting systematic reviews and developing good practice guidelines (where appropriate) are resource intensive and that research in this area is rapidly evolving, it may be prudent to develop expert consensus statements. Dietitians in our study identified cardiometabolic disease prevention/management and personalized nutrition for cancer prevention as the first and second priority topics for future CPGs. The latter is a highly feasible topic for future CPGs given that a systematic review with evidence grading on this topic has already been completed recently [

37]. This review demonstrated “moderately strong evidence (Grade BBB)” for the association between the 10p14 locus and elevated colorectal cancer risk when processed meat consumption is high [

37]. In terms of clinical applications, these findings suggest that depending on genetic variation at the 10p14 locus, it may be particularly important for some patients to limit their processed meat consumption for colorectal cancer risk reduction.

More systematic reviews would also be helpful in informing the development of evidence-based educational resources, especially as scientific validity was highlighted as an important component of training on nutrigenomics by respondents. When establishing the levels of evidence for certain gene–diet interactions in future CPGs, a modified version of the framework proposed by Boffeta et al. has been recommended for use [

26]. Partnerships with organizations such as Dietitians of Canada, Practice-Based Evidence in Nutrition (PEN), and dietetic curriculum developers could be useful in developing educational/training resources and increasing awareness of nutritional genomics among nutrition care providers.

As with all research, there are some limitations that exist in this study. Our questionnaire did not include questions on respondent demographics; therefore, we are unable to evaluate if our sample was representative of HCPs across Canada or describe personal factors that may have influenced responses such as the practice setting or number of genetic tests administered. In addition, the non-RD group was heterogeneous and included both regulated and non-regulated HCPs. The small numbers of the different types of non-RD HCPs limited our ability to conduct further subgroup analyses. Although the current results can only be generalized to dietitians and other nutritional care providers in Canada who work directly with patients, HCPs who do not work directly with patients are unlikely to encounter nutritional genomics in their practice and therefore may not be as willing to seek training in this area. Respondent bias is also a potential limitation of survey-based research [

38]. Nutrition providers with a particular interest in nutritional genomics could have been more likely to respond to the survey. In addition, since survey questions could be skipped, some respondents chose to skip certain questions leading to different and sometimes smaller sample sizes for different questions. Due to this, it is possible that some statistically significant results may have been missed. Despite these limitations, this study provided a comprehensive and robust overview of the specific educational and training needs of various nutrition providers offering nutrition advice in Canada related to the increasingly popular science of nutritional genomics.