INTRODUCTION

Anxiety is a prevalent and inherent emotional state characterized by feelings of tension and worry, accompanied by physiological changes such as increased heart rate, rapid breathing, sweatiness, and restlessness [

1]. Anxiety is a complex experience that can vary in intensity from mild to severe [

1]. Anxiety generally involves two complementary concepts, namely trait anxiety, which pertains to an individual’s personality, and state anxiety, which is rather linked with different circumstances [

2,

3].

Anxiety among undergraduate students has increased over time, with 35% to 43% showing signs of anxiety [

4]. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has also greatly contributed to increased anxiety among students, with prevalence being significantly higher during and after than before the pandemic [

4]. Studies have demonstrated that anxiety can negatively impact an individual’s abilities to recall information, acquire various skills, and perform, perhaps due to its impact on memory and learning [

5]. Students may experience anxiety in a variety of contexts, including during supervised learning activities such as simulations [

6]. Simulations are learning experiences reminiscent of authentic clinical situations taking place in a supervised environment [

7]. Simulation activities normally require students to assess a patient and intervene while being monitored on their performance [

7]. While this experience can be seen as a clinical reasoning and skill-building opportunity, it can also be perceived as a threat, inducing anxiety among students [

5]. Early research on anxiety reported that it is possible to reduce anxiety using social learning theory and appropriate pedagogical approaches [

8].

Simulation-based learning has become a growing part of health professionals’ education pre- and post-licensure. Studies with nursing students have demonstrated that simulations are a potent teaching-learning tool to augment students’ knowledge [

9], critical thinking [

10], clinical reasoning [

11,

12], clinical competence [

9,

13,

14], communication skills [

9,

15,

16], confidence [

13,

17], and motivation [

9,

18]. In the field of dietetics, simulations are also used to help students develop clinical competencies [

19]. Furthermore, the updated Integrated Competencies for Dietetic Education and Practice (ICDEP [

19]) point to an increased need to use simulations as a means to support the development of dietetic competencies to prepare future dietitians for entry into practice. Indeed, structured simulations with standardized patients are especially helpful as they allow educators to determine, based on observation, whether the learner knows how to perform at a competent level in various situations imitating the practice of dietitians [

19].

However, to our knowledge, there is no existing research assessing perceived anxiety levels towards simulations among dietetic students or dietitians. Since little is known about anxiety and simulations in this population, this pilot study aimed to assess dietetic students’ anxiety levels before and after a series of simulations and to document students’ perceived sources of anxiety while completing simulation-based learning activities.

METHODS

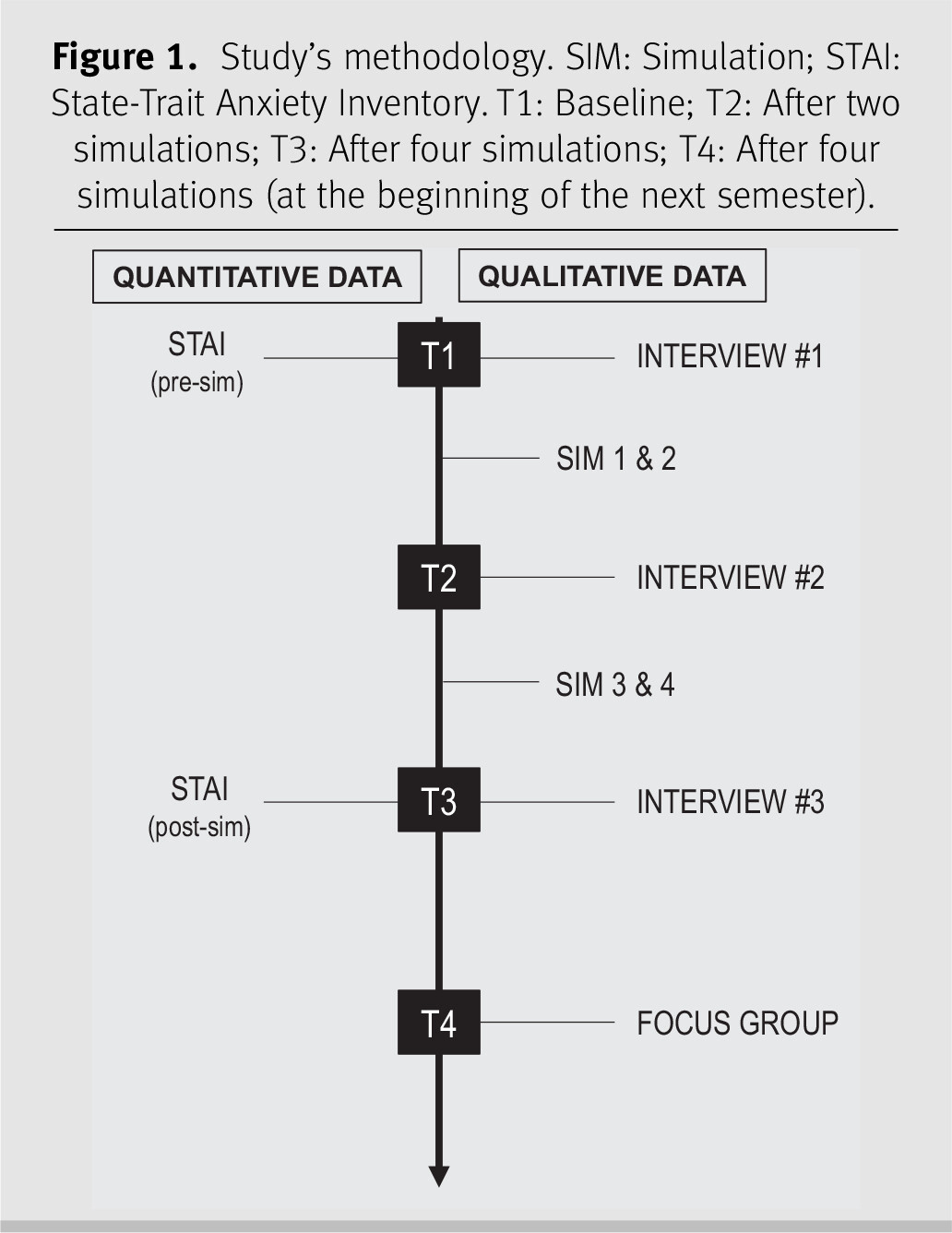

A convergent mixed-method approach was used to address the study’s aim [

20]. Quantitative and qualitative approaches were used concurrently for data collection [

20]. Data sets from both approaches were analyzed separately and compared at the end of the analysis process.

The study involved participating in a series of four simulations, completing online questionnaires, as well as engaging in individual interviews and a focus group discussion. The four simulations have been previously described and are summarized in Supplementary file 1 [

21].

1 Data collection took place over 5 months, from 5 September 2017 to 31 January 2018. The methodology was pilot-tested in January 2017. An overview of the study timeline is presented in

Figure 1.

Study participants

Participants were recruited from a cohort of 28 third-year students enrolled in the Nutrition Assessment compulsory course as part of the Honours Bachelor of Food and Nutrition Sciences program at the University of Ottawa during the fall semester (6 September – 6 December) 2017. All students enrolled in the course were invited to participate in the study and had the choice to take part in both the qualitative and quantitative components or solely in the quantitative component. Due to the limited pool of students, participants in the qualitative component of the study were selected on the sole base of willingness to participate.

Quantitative component

Data collection

Students completed an online questionnaire using SurveyMonkey (Momentive Inc., San Mateo, California, USA) at baseline (T1) and after the four simulations (T3). The questionnaires included questions on demographic variables as well as the French version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [

22]. The STAI is a psychometric test developed by Spielberger (1983) that is widely used in different populations and is a gold standard to evaluate trait and state anxiety [

2]. Trait anxiety refers to a relatively enduring and stable personality trait that predisposes individuals to experience anxiety consistently across various situations and throughout their lives [

2,

3]. On the other hand, state anxiety refers to the transient and situational experience of anxiety that is directly related to a specific circumstance, event, or stressor [

2,

3]. Both trait and state anxiety contribute to an individual’s overall experience of anxiety, with trait anxiety representing an individual’s baseline level of anxiety predisposition and state anxiety representing the fluctuating levels of anxiety experienced in response to specific circumstances [

2,

3]. The STAI consists of 40 self-report items answered on a 4-point Likert scale. To assess trait anxiety, questions such as “

How do you generally feel?” were asked with the response options “Not at all” to “Very much so,” while questions like “

How do you feel at this moment regarding …” with the response options “Almost never” to “Almost always” were asked to assess state anxiety [

2]. Total scores were calculated for both state and trait anxiety by summing the answers of associated items. Lower scores on the STAI indicate lower perceived anxiety, with scores <36 being classified as very low, scores between 36 and 45 being classified as low, scores between 46 and 55 being scored as average, scores between 56 and 65 being classified as high, and scores >65 being classified as very high [

23]. The fidelity and validity of the French version of the STAI were similar to the original English version [

22].

Data analysis

Data are reported as medians and interquartile ranges. Wilcoxon signed-ranked test was used to compare pre- and post-simulation medians of trait and state anxiety. Spearman’s correlations were used to assess the association between prior experiences (i.e., in simulation or interacting with patients in clinical settings) and anxiety. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 (International Business Machines Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA. 2018), with P ≤ 0.05 considered significant.

Qualitative component

Researchers’ characteristics and reflexivity

The principal investigator of this study (IG) was the professor of the Nutrition Assessment course. IG was not involved with data collection and was not present when the simulations took place. At the time of the study, MR was a graduate student conducting a Master’s degree in Education. MR was responsible for data collection and analysis. MR had no conflict of interest with the participants enrolled in the study and was not involved with the Nutrition Assessment course development, delivery, or evaluation. AB was a doctoral-level research assistant that helped with data analysis and had no contact with students.

Data collection

Each student participated in three semi-structured individual interviews (see Supplementary file 2) and one focus group (see Supplementary file 3). Individual interviews were conducted at three times points, namely at baseline (T1), after two simulations (T2), and after four simulations (T3), while the focus group was conducted at the beginning of the next semester, after the four simulations (T4). Individual interviews and focus group guides were informed by previous studies on factors that can influence anxiety [

2]. These guides contained questions on feelings before and after the simulations, leading participants to discuss anxiety. Individual interviews also directly addressed sources of anxiety. MR conducted all individual interviews. MR and AB conducted the focus group discussion. Following Bloom’s (2001) recommendations, one researcher took notes while the other asked questions [

24]. To encourage discussion between participants, questions were one-dimensional, open-ended, and concise [

25].

Data analysis

To facilitate thematic analysis, individual interviews and the focus group discussion were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by MR and subsequently verified for clarity and accuracy by AB. MR and AB independently performed thematic analysis using NVivo QSR software (QSR International Pty Ltd. Burlington, Massachusetts, USA. Version 11, 2015). Based on previous research by Spielberger [

2], themes were divided into two categories, namely individual factors and external factors that could influence anxiety. There were two pre-established individual factors, specifically stress and self-confidence, and two pre-established external factors, observers and unknown situations. The process of deciding on these pre-established themes was based on a discussion and consensus between the three researchers. Themes were also inductively derived from data. Krippendorff’s coefficient was calculated to assess inter-rater reliability [

26]. MR and AB met to discuss emerging themes and possible discrepancies. IG was available to settle any disagreements.

DISCUSSION

Using a convergent mixed-methods approach, this pilot study aimed to document dietetic students’ perceived anxiety levels, along with common sources of anxiety encountered during simulation-based learning activities. The quantitative and qualitative findings complemented each other, indicating a reduction in perceived anxiety levels from pre- to post-simulations and identifying various individual and external factors contributing to students’ levels of anxiety towards simulations.

As previously mentioned, state anxiety pertains to the temporary feeling of anxiety associated with a specific situation, in this case, the simulations [

2,

3]. Based on the social learning theory, we hypothesized that students’ anxiety levels would decrease over time as they become accustomed to the simulations [

8]. In line with our hypothesis, quantitative results showed that mean state anxiety levels decreased from average at the pre-simulation stage to very low post-simulations [

2].

Our results are consistent with the findings of two recent systematic reviews supporting the efficacy of simulations in reducing anxiety and enhancing self-confidence among nursing students when performing nursing duties or managing patients [

17]. A pilot study evaluating the effects of simulation-based interprofessional education also demonstrated positive outcomes concerning students’ confidence to engage in interprofessional practice settings [

27]. While most students reported decreased state anxiety levels from pre- to post-simulations, over one-third of them still reported stable or increased state anxiety from pre- to post-simulations. It is possible that students reporting stable or increased state anxiety levels had less positive simulation experiences, which may be linked to personality type, learning style, and the perception that the simulations were evaluated [

28].

Future studies are needed to confirm whether our findings are replicable using different simulation types, including simulations involving several professions. It is also important for future research to evaluate the long-term effects of simulations, for example, assessing students’ anxiety levels and perceptions during and after completing their clinical practicum placements.

Some sources of anxiety identified by students, such as patient characteristics, feedback from observers, level of preparation, and academic settings, have not been previously reported in the literature. As in our study, another study conducted with paramedic students reported that the presence of the instructor during simulations contributes to students’ anxiety levels [

29].

In our bilingual university, the preferred language of the patient was a source of anxiety reported by some students. Dietetic learners are encouraged to actively offer services in the preferred language of their simulated client [

30] to prepare them to provide culturally safe care [

19]. Although both official languages are frequently spoken, some patients may be unilingual. Students are aware of this reality, and some have reported being stressed about meeting the patient’s needs because they feel uncomfortable delivering care in the patient’s preferred language. While prior research did not identify patient language or cultural background as a source of anxiety, students’ unfamiliarity or discomfort is likely associated with some additional anxiety.

To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the impact of simulations on anxiety levels among dietetic students. Unlike previous studies that solely collected qualitative data at the end of simulations [

31–

34], our study used a mixed-methods design to collect both qualitative and quantitative data at multiple time points over 5 months. However, there are several limitations to consider. First, this was a pilot study with a small sample size and a potential risk of bias. The study should be repeated in larger groups of dietetic students. Second, students who volunteered to participate, especially in the qualitative section, may not be representative of all dietetic students. The topic of the interviews and focus groups required students to share personal information and placed participants in a vulnerable situation. Students who participated in the study may have been more confident or may have lower anxiety levels than the general target population. Third, data collection was conducted in 2017–2018, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the impact of the pandemic on students’ stress and anxiety levels, our results may not be replicable in future cohorts as students may respond differently to simulations. However, these findings are still highly relevant since the pandemic induced a scarcity of practicum opportunities for dietetics learners, and educators have been desperately looking for viable and stable ways to enhance competency learning options for future dietitians [

35].

While our study focused on the experience of dietetic students during simulation-based activities, several concepts highlighted by our findings (e.g., dealing with cultural differences) may be applicable to other disciplines. Furthermore, gaining a deeper understanding of the relationship between teaching methods like simulations and students’ anxiety levels will inform strategies to better prepare them for clinical practicum placements and future professional environments. Given the elevated prevalence of mental health issues in work settings [

36], a planned transition from academia to the workplace, involving a sequence of competency-building simulations, may empower students to feel confident and well-prepared to face these challenges and embrace opportunities.

RELEVANCE TO PRACTICE

Research on simulation-based learning is relevant to both dietetic students and educators. In particular, as anxiety can interfere with students’ abilities to recall information, acquire various skills, and perform, exploring the levels and common causes of anxiety while learning clinical competencies through simulation-based learning is essential [

6,

17,

34,

36,

37]. Anxiety has been identified as a factor negatively impacting students’ performance by clinical practicum placement preceptors [

38]. Based on the findings from this pilot study, we recommend that educators adopt the following pedagogical approaches when using simulations to enhance the effectiveness and value of this educational experience for learners: (

i) since students preferred to engage in simulations without educators being present, educators can encourage peer-feedback, feedback from actors and facilitators, feedback from educators post-simulation using simulation recording, and asynchronous simulations with debriefing; (

ii) since preparing questions for simulated interviews was beneficial in decreasing stress levels, educators could advise students to prepare a list of potential questions in advance of simulations; (

iii) since most students viewed simulations as a formal evaluation, educators could reassure students that simulations are an effective pedagogical tool to support their learning and explain why. While our findings suggest these approaches may be useful, future studies should evaluate their effectiveness. Furthermore, since the ICDEP 2020 [19)]point to the need for ongoing competency development for dietitians post-licensure, this study points to recommendations that can translate into effective pedagogical strategies for dietetic educators to reduce anxiety of learners and facilitate competency development with simulation to the benefit of both dietetic trainees and dietitians.