INTRODUCTION

Willet and colleagues [

1,

2] argued that “food systems have the potential to nurture human health and support environmental sustainability; however, they are currently threatening both” [

1, p. 1]. In aggregate, current global food systems provide safe and abundant food. However, they also have led to significant negative environmental and social outcomes that manifest uniquely according to context. From global and environmental perspectives, food systems contribute to climate change [

1,

3,

4], with 20%–50% of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture [

5,

6]. Food systems also contribute to biodiversity loss, interference with global nitrogen and phosphorus cycles, and depletion of freshwater [

1,

7,

8]. Further, they perpetuate social injustices that affect human agency and livelihoods [

9]. In today’s food system, access to food is unequally distributed; more than 820 million people lack sufficient food globally [

1,

10], and food insecurity exists in countries of all income profiles [

9,

11]. Food systems also engender the adoption of unhealthy diets [

1,

12–

14], thus reducing health and quality of life [

1]. Conversely, more environmentally and socially sustainable dietary patterns can support health, suggesting important co-benefits [

15].

Food systems are embedded in both social and ecological systems from local to global and are therefore inherently multi-disciplinary, -sectoral, and -scalar in nature. This quality leaves food systems vulnerable to the tragedy of the commons, whereby individuals and groups draw from food systems resources, guided by self-interest, in a way that is contrary to the common good. Leadership in various sectors, including health, is necessary to ensure collective responsibility for sustaining food systems, and clarity around roles can help facilitate this. Recommendations have been made for public health professionals in the United Kingdom to support healthy and sustainable food systems [

16]. However, despite the importance of their possible contributions, like many health professionals (including physicians, nurses, and paediatricians) [

17–

19], Registered Dietitians and Nutritionists (in this article referred to collectively as RDs for brevity, but inclusive of a diversity of titles used across jurisdictions) experience barriers at the personal, social, and professional levels that prevent them from contributing fully to sustainable systems. This contextualization allows us to better understand and position the roles of RDs in sustainable food systems (SFS).

The British Dietetic Association posits that RDs “

should be leading discussions on how food behaviours can affect both health and the environment” [

20]. Many RDs are ready to contribute; they have a comprehensive understanding of the issues, indicate that SFS is a relevant topic to practice, and actively participate in international dialogue [

21]. However, translating knowledge to practice is complex and many more are unsure of where to begin.

MAPPING THE ROLES OF RDs WITHIN THE FOOD SYSTEMS LANDSCAPE

The purpose of this perspective article is to map the landscape of existing and potential opportunities for RDs to leverage change for more SFS and discuss emerging approaches and barriers. We draw from research capturing how RDs define their role in SFS [

21,

22], reports [

23], and the small body of peer-reviewed literature available [

24–

28]. As such, it presents a theoretical proposal as well as professional self-determination, informed by collective expertise. The article also highlights for non-RDs, the role of nutrition colleagues as collaborators in this important transition.

Sustainable food systems “

deliver food and nutrition security for all in such a way that the economic, social and environmental bases to generate food security and nutrition for future generations are not compromised.” [

29 p. 1]

Sustainable diets (SD)

“are those diets with low environmental impacts, which contribute to food and nutrition security and to healthy life for present and future generations. Sustainable diets are protective and respectful of biodiversity and ecosystems, culturally acceptable, accessible, economically fair and affordable; nutritionally adequate, safe and healthy; while optimizing natural and human resources” [

30 p. 7].

Sustainable diets contribute to and are supported by SFS [

31]. Both are relevant to the work of RDs, and for brevity SFS is used to denote these interrelated concepts.

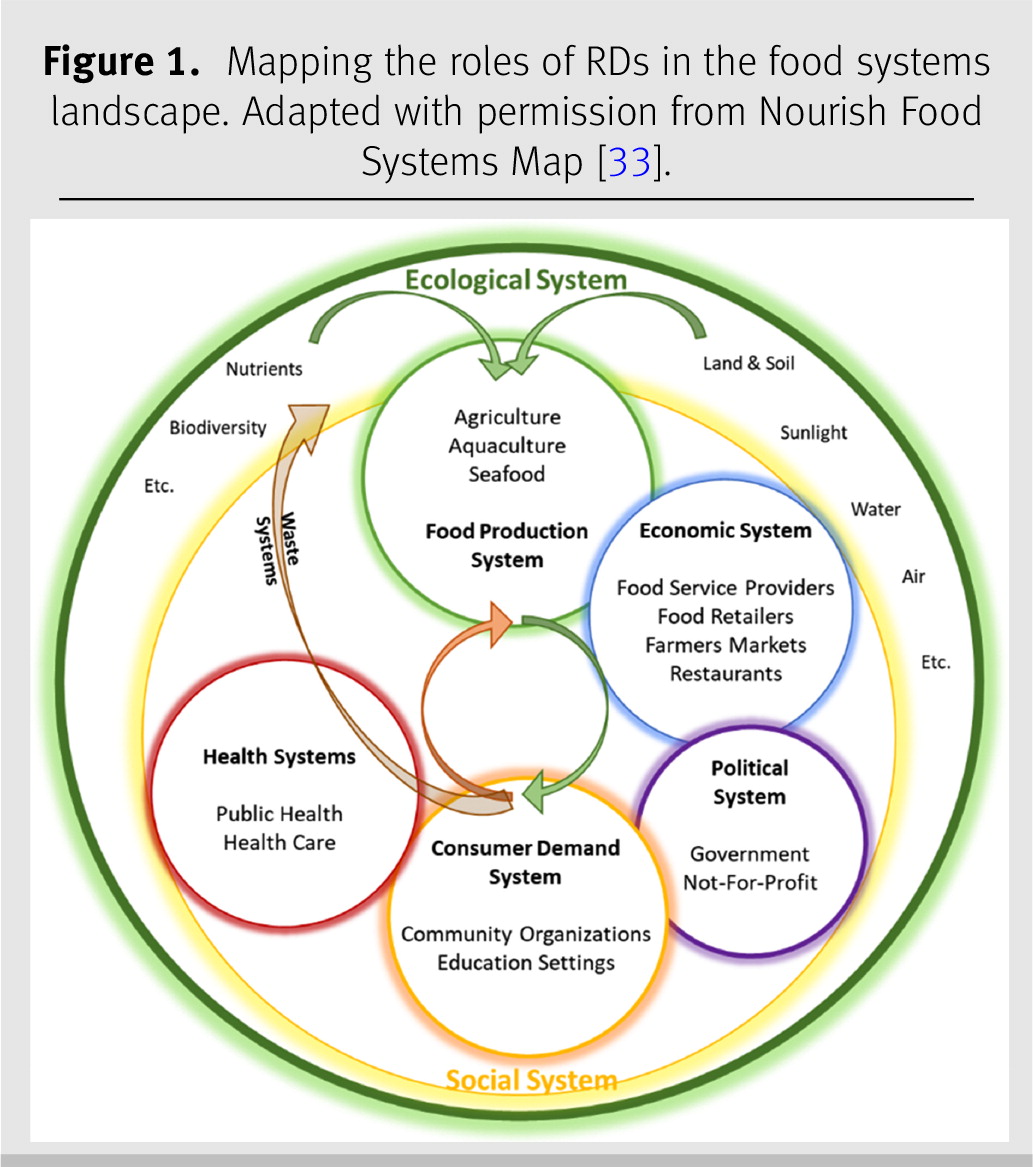

Food systems can be conceptualized as complex and dynamic systems encompassing interrelated subsystems (

Figure 1). This aligns with dietitians’ recognition that health is dependent on, and achieved within, the socioecological context [

32]. The subsystems included in

Figure 1 are adapted from Nourish [

33], and they are not an exhaustive list, but rather orient the reader to the breadth of RD integration throughout food systems.

While Canadian dietetic roles tend to be conceptualized as divided into four typical areas of practice (clinical, food service, community, or industry), in this article we re-offer roles according to entry points in food systems. RDs have roles within health, consumer demand, political, economic, and food production systems. Roles among regions and employers vary and the following examples must be interpreted in the local professional context.

Within health systems, RDs are employed in public health agencies, focusing on health promotion and disease prevention through nutrition-based programming, and in hospitals, long-term care facilities, and private clinics, providing nutrition care to clients and managing institutional food procurement and provision.

In consumer demand systems, RDs work in community-based settings supporting food security, literacy, and culture. This is done through, for example, community- and school-based programs.

In political systems, e.g., government or not-for-profit, RDs contribute to food and nutrition policy to maximize public health outcomes.

In economic systems, RDs work with food service providers, food retailers, farmers’ markets, and restaurants. In these roles, they drive innovations that promote healthier food options through marketing, promotions, sales, and menu and recipe development.

In food supply systems, RDs work directly and indirectly in agriculture, aquaculture, or seafood sectors. They work as food producers with producer organizations to promote, market, and sell food products.

Within these roles across food subsystems, RDs can apply their competence (the cumulative expertise and skills that RDs attain in education, training, and practice), to “

appl[y] the science of food and nutrition to promote health, prevent and treat disease to optimise the health of individuals, groups, communities and populations” [

34].

MAPPING THE WAYS RDs CONTRIBUTE TO SFS

Across the various subsystems and roles, RDs can and do use several strategic approaches to tailor their SFS work to their roles and competences. Strategic approaches are categorized into: collaboration, advocacy, policy change, knowledge translation, knowledge dissemination, research, and management. Although considered here separately, these strategic approaches can be combined to create synergies and stronger leverage for change.

Collaboration is crucial to forward global goals for SFS [

1]. Working in teams across disciplines is common for RDs and some already leverage these skills to develop mutually beneficial results for SFS [

26]. Examples include: Food Charters or regional food and nutrition strategies that guide collective action [

35–

37], food waste reduction strategy teams [

38,

39], and nutrition-sensitive food production advocacy [

40].

In several food subsystems, RDs can advocate for policies that protect soil quality, ensure sufficient livelihoods, and increase equity in access to food, highlighting the co-benefits to nutrition outcomes [

9,

41,

42]. Likewise, RDs can highlight for nutrition colleagues the environmental and social co-benefits that arise from improved nutrition [

22]. Canadian RDs have been actively advocating for national [

25,

43] and sub-national [

37] food policies that apply a SFS lens. Importantly, RDs must, and most already do, consider the local sociocultural and environmental contexts of their advocacy efforts to avoid well-intended but inappropriate recommendations [

24].

RDs in food service and health care institutions are creating policies that mandate more sustainable protocols, such as increasing sustainable food procurement and decreasing food waste [

37]. In public health, RDs already contribute to policies guiding the adoption of more sustainable dietary patterns, such as recommending moderate food consumption, plant-based dietary patterns, reducing ultra-processed food consumption, and reducing food waste [

41].

RDs seek to empower their clients, patients, communities, and populations to understand and enjoy food through interpreting the science of food and nutrition, translating and disseminating it through audience-appropriate information [

44]. For example, RDs are helping to translate ecological data about the climate impact of specific foods or dietary patterns into food service menus without compromising nutritional adequacy [

45]. Although knowledge does not necessarily lead to behaviour change, there is support for the role of knowledge dissemination in contributing to SFS [

21,

24,

46,

47]. In health systems, where clinically and socially appropriate, RDs have the opportunity to counsel patients to optimize their nutritional health in the context of planetary health [

48,

49]. The abundance of conflicting public messaging creates confusion for consumers [

50]. This is an opportunity for RDs to separate facts from fiction [

25]. Knowledge dissemination can take multiple forms, through, for example: food manuals that illustrate culturally appropriate foods using plants indigenous to the region, which can be used for community education [

51], using gardens as a teaching tool [

52], and showcasing the value of community-based food systems alongside food systems at larger scales [

53]—this diversity of small and large scales supports more resilience in food systems [

54].

Internal to the profession, integrating SFS into the curriculum contributes to competence development, and evidence from Australia indicates students are receptive [

46]. Some universities are integrating food waste reduction management into existing courses, and engaging students in delivering plant-forward eating workshops [

55], whereas others have developed specific courses [

56] or modules [

57] for students and staff [

58] to explore SFS as separate topics. These efforts increase the confidence of future RDs to tackle issues of sustainability.

Food systems that do not support human health are not sustainable [

59], and RDs are crucial members on interdisciplinary research teams investigating the relationships between sustainability and food, ensuring that nutritional impact is understood and counted. For example, industry researchers crafting solutions to minimize food production waste are collaborating with RDs for insight on nutritional impacts and appropriateness to consumers and contexts [

60].

Organizational leadership is critical to ensure meaningful sustainability outcomes [

17]. Those in administrative positions can apply management skills to systematize more sustainable menus; foster a culture of sustainability-thinking within the organization; establish a sustainability management team; conduct waste, energy, and water audits; mandate protocols that minimize food and packaging waste; and co-create clinical practice standards that also account for sustainability [

22,

24,

61].

While some RDs [

21] and Dietetics Associations [

20] indicate RDs are well positioned to provide leadership across the abovementioned roles and approaches, this does not imply sole responsibility [

21]. This paper is one effort to capture the perceived and potential opportunities to contribute to collaborative work.

BARRIERS TO INTEGRATING SFS INTO PRACTICE

Some RDs have reservations about whether sustainability issues are within their scope of practice, core to practice, or a specialization [

21]. Exploring these tensions is important and may offer insight into high-leverage action.

Many Canadian RDs express a lack of confidence, feeling inadequately equipped to determine what evidence is well-supported, what to recommend to their clients and colleagues [

22,

24], or which high-quality training opportunities exist. This reflects a need for more comprehensive competency development during training [

26,

47,

62]. Because dietetic curricula are already under tight constraints, and supervisors may have insufficient SFS competence to support trainees [

62,

63], inserting more mandatory curriculum is challenging. Creative solutions are required.

One solution may lie in reframing the obligations of the profession. Dietetic practice evolved to prioritize individual health while deprioritizing the socioecological system [

25,

64]. Training is generally oriented to working with autonomous, self-regulating clients, rather than identifying and addressing [

25] social [

65] and ecological determinants [

66] of health. A more SFS inclusive pedagogy could reframe competencies to support RDs to “

appl[y] the science of food and nutrition to promote health, prevent and treat disease to optimise the health of individuals, groups, communities and populations” [

34]

within the context of the health of the socioecological systems (our proposed addition to the definition). Such a reframing may drive integration of SFS approaches into dietetic training.

RELEVANCE TO PRACTICE

Dietitians are strategic partners in collaborative action for sustainable development. Examining the sustainability of the entire food system can be paralyzing. However, this paper posits that meaningful contributions can be made by integrating SFS into existing roles and individual competence of RDs. The breadth and extent of RDs’ integration throughout food systems can lead to a collectively systemic impact, and facilitating action across multiple systems (e.g., political systems, economic systems, etc.) is more likely to result in lasting systemic change [

17]. Furthermore, many RDs are already engaged with SFS, contributing competently through a combination of approaches. They serve as examples to guide practice in an environment where specific guidelines do not exist, and may never be appropriate, given the highly contextual nature of sustainability.

While many dietitians are ready to contribute, training gaps and competing forces obstruct more systematic contributions to SFS and limit the potential for greater achievements. To engage RDs in this work, these barriers need to be addressed.

This perspective draws from a limited body of peer-reviewed research and reports. Future research is needed to explore innovative models and establish effective approaches for integrating SFS into dietetic training programs.