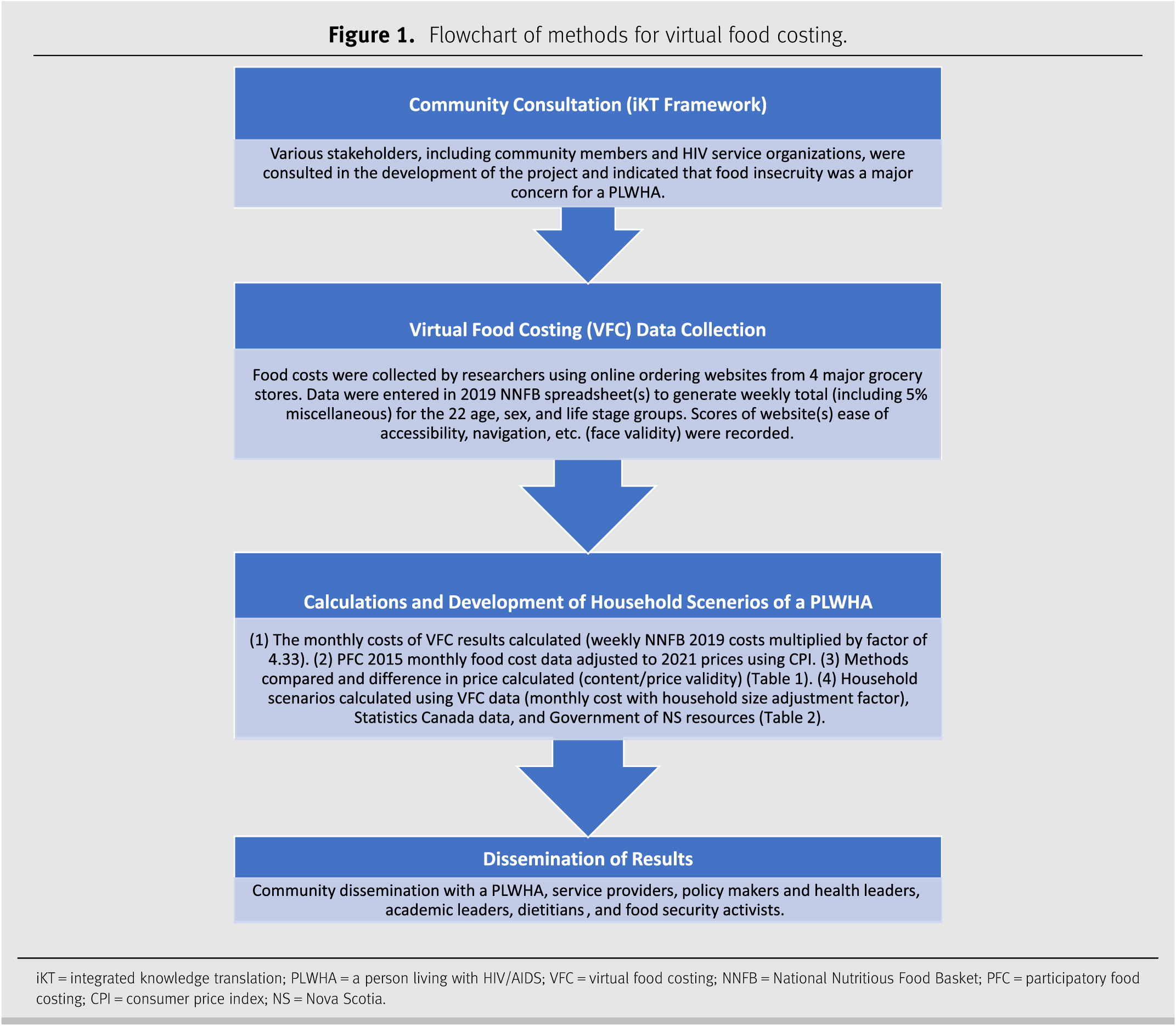

Virtual food costing (VFC) was developed as an alternative food costing method (

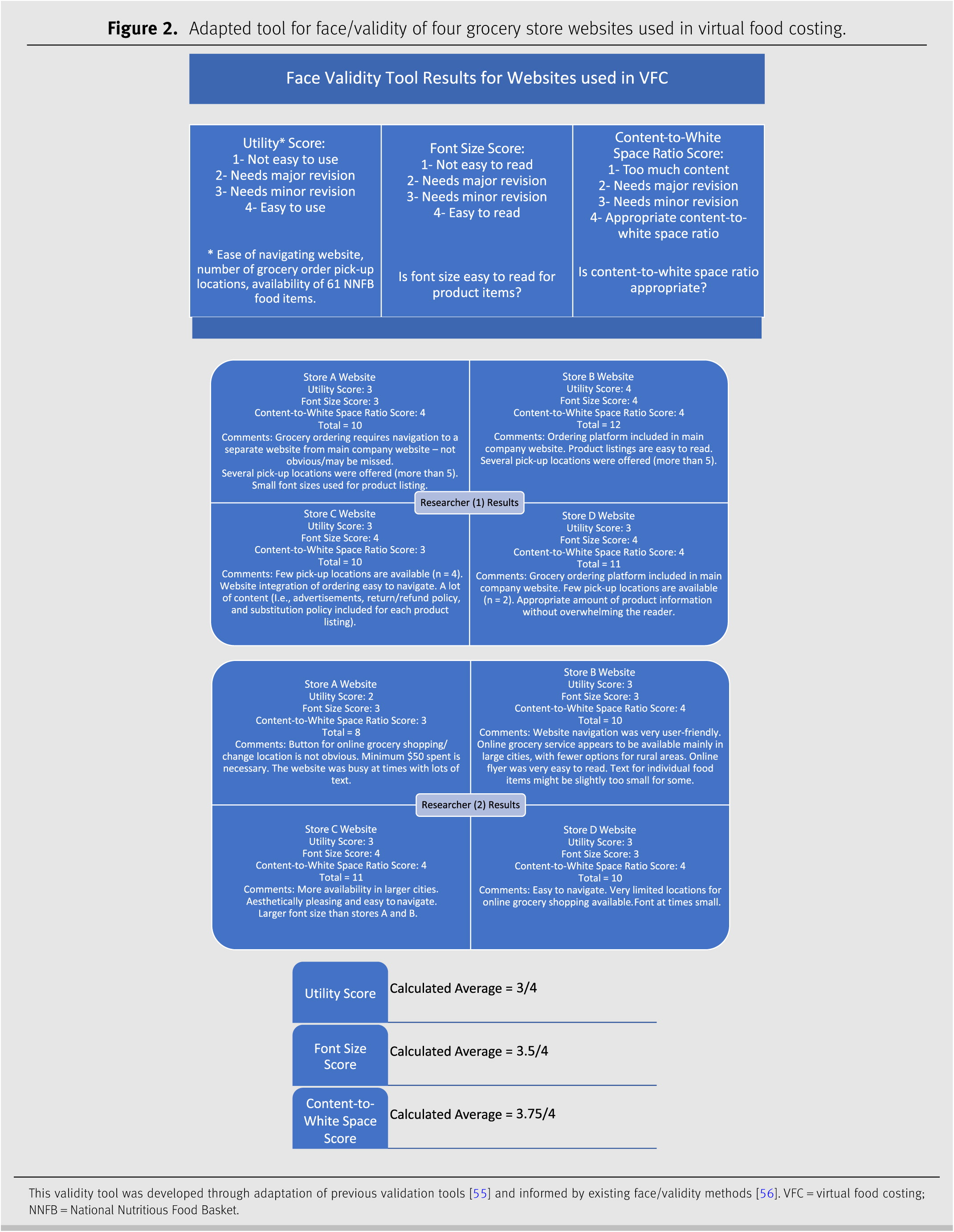

Figure 1) during the COVID-19 pandemic in response to restrictions to in-person grocery shopping/food costing, as it was considered a safer option for both researchers and immunocompromised community members. Unlike in-person PFC, VFC was conducted exclusively online, and given that VFC is a novel method, the research team decided to conduct the data collection themselves. This means our study was not participatory as initially intended but, rather, community-based, as stakeholders and community members asked for this project and offered consultation throughout the study but did not take part in data collection. As part of VFC as a novel method, face/content validation was conducted as a pre-test towards preliminary assessment of the effectiveness of VFC. In efforts to assess both user experience and the potential for VFC to become participatory in the future, the researchers conducted face/content validation while navigating each website platform (n = 4). Over a two-week period in June 2021, two researchers (AC, JM) collected food prices from the websites of four major retailers in Nova Scotia. The NNFB tool (NNFB Excel spreadsheet [

20]) was used to calculate the cost of the NNFB for the 22 age, sex, and life stage groups. Using the weight (per kg) of each item, the researchers (AC, JM) recorded the least expensive option offered for each of the 61 NNFB grocery items [

20]. For price validation (

Table 1), the data collected using VFC was compared to 2015 PFC data [

23], which was adjusted for 2021 inflation using a consumer price index (CPI) calculator [

24] based in Canadian data.

Using the above outlined methodology, we calculated six different household scenarios for Nova Scotia (

Table 2), with one individual living with HIV/AIDS in each household. Monthly household income was estimated based on employment status and eligibility for federal and provincial Income Assistance and benefits [

25–

31]. To calculate estimated household expenses, four components of the MBM [

32] were used for clothing, transportation, shelter, and miscellaneous expenses. The MBM expense estimates represented Nova Scotians across the province, including both rural and urban centre populations [

32]. Food expenses were determined using the results of VFC. The 2019 NNFB for one week, plus 5% for miscellaneous costs, was calculated for the 22 age, sex, and life stage groups [

20]. We then calculated the monthly cost of the NNFB by multiplying the weekly total by a factor of 4.33 [

23]. For the household scenarios (

Table 2), the monthly cost of the NNFB for each household member was added, and the total was multiplied by the appropriate household size adjustment factor [

23]. Households with a PLWHA must also consider the cost of antiretroviral medications [

33], dispensing fees [

33,

34], a daily multivitamin [

35], and an additional 10% of energy (food) intake [

36,

37]. A 10% increase in food intake may be recommended, since a PLWHA can have up to a 10% increase in total energy expenditure [

36,

37]. To best represent the cost of the 10% increase in energy intake for a PLWHA, 10% of the cost of the monthly NNFB was added for one person in the household. This method could be adapted for costing other special diets that require additional dietary expenses. In Nova Scotia, dispensing fees are paid for each 90-day supply of antiretrovirals, totalling $45 (CAD) annually [

33]. Persons who are registered for Income Assistance can be reimbursed for dispensing fees but may be charged up to $5 (CAD) for each prescription filled [

34]. The dispensing fees were represented in the household scenarios ($45 divided by 12 for monthly total) for those who would be responsible for paying dispensing fee costs. To determine the remaining income of each household, the cost of shelter, clothes, transportation, NNFB, daily multivitamin, medication dispensing fees (if applicable), and miscellaneous expenses were deducted from the total monthly income (

Table 2).