INTRODUCTION

In 2021, immigrants represented 23% of, or 2.3 million, people in Canada, the largest proportion since the Confederation in 1921. It is estimated that by 2041 immigrants could represent up to 34% of the Canadian population [

1]. The growing immigrant population face new and unique challenges [

2,

3], and multicultural knowledge and skills are required to provide equitable, culturally competent care [

4,

5]. A culturally competent healthcare practitioner understands the importance of social and cultural influences on patients’ health, beliefs, and behaviours, and they consider how these factors interact to provide the most impactful care [

1,

2,

6,

7].

Cultural competency training is now recognized and required to be formally integrated into dietetic curricula by accrediting dietetic bodies in Canada and the United States [

8,

9]. However, a 2015 survey of 3

rd and 4

th year Canadian nutrition and dietetic students indicated gaps in cultural competence training and education which left them unprepared as new practitioners [

10]. It is imperative that registered dietitians (RDs) be equipped with the tools to develop cultural competency before they reach practice so that they can equitably and efficiently serve clients from diverse cultures, thus helping to address health disparities among immigrant populations [

6,

7].

Purpose

This study presents an innovative programme, Linking Immigrants with Nutrition Knowledge (Project LINK), a service-learning cultural competence training programme with the goal of developing and measuring the development of cultural competence in dietetic students. This paper reports the mixed methods evaluation of the association between participation in Project LINK and improvement in cultural competence.

METHODS

Participants and recruitment

Second-year nutrition and dietetic students enrolled in the University of Saskatchewan’s (USASK) nutrition and dietetic programme participated in Project LINK in 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014. Project LINK was a required component of the course NUTR 310.3: “Food, Culture and Human Nutrition.” Although all students participated in all course requirements, they were not required to participate in the research study. All students were invited to participate in the study; however, only those who provided informed consent and agreed to complete the pre- and post-programme assessments were included.

Immigrant and refugee families were recruited in July and August each year. Recruitment of these families was co-ordinated with the assistance of Saskatoon Open Door Society and the Saskatchewan Intercultural Association (settlement agencies) in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Families selected were recent immigrants or refugees to Canada (< 5 years), had sufficient English proficiency, contained a range of ages (including children), and represented a variety of cultures. Over the 4 years of the programme, 14 immigrant/refugee families were recruited and consented to participate.

Ethical approval for this evaluation was obtained from the University of Saskatchewan Research Ethics Board before implementation (USask REB BIO-09-197). Additionally, students were required to undergo a criminal record check to work with vulnerable populations.

Project LINK active-learning module

Project LINK was implemented in the fall semester of each of the 4 years. Enrolled students were briefed on the purpose and components of Project LINK.

Students participated in lessons on cultural competency and intercultural communication as well as a workshop, hosted by the project team, where dietetic students interacted with international graduate students in a role-playing scenario to implement their learnings in a semi-hypothetical situation before beginning any components of Project LINK and entering into ‘real-life’ scenarios. In groups of two, students were partnered with an immigrant/refugee family. The project was designed to ensure students and families could meet frequently during the semester to develop rapport and connection. Four semi-structured opportunities for interaction between student pairs and families were provided: (1) an orientation meeting, (2) rapport developing meeting, (3) a grocery store tour, and (4) a cultural cooking session. Dietetic students were initially introduced to partner families through an informal evening event. Students were instructed to plan rapport developing meetings with their partner family to allow students to gain a better understanding of assigned families’ culture and food preferences/choices. For the purpose of observation and guidance, students accompanied assigned families during a grocery shopping trip. Students were encouraged to be open-minded and aware of their own biases (e.g., avoid making or verbalizing judgments about food choices); however, students were encouraged to assist them in selecting healthy, budget conscious foods. Finally, at the project end, students and partner families prepared a dish celebrating the family’s culture together.

For most dietetic students, this was their first experience with service-learning and the first opportunity for meaningful interaction with culturally diverse immigrant and refugee families. Learning objectives for the dietetic students were to: (1) gain skills in intercultural communication, (2) understand the challenges, particularly those related to food and nutrition, faced by newcomers to Canada, and (3) participate in the practical application of theories learned in class related to the roles of culture, religion, nutrition transition, and acculturation in shaping the diet of immigrants and refugees.

DISCUSSION

Project LINK provided the academic platform to support dietetic students in learning how culture impacts dietetic practice, such as through the provision of culturally appropriate care and the significant influence of culture in our food choices. The dietetic students who participated in Project LINK gained skills and built meaningful relationships with participating families.

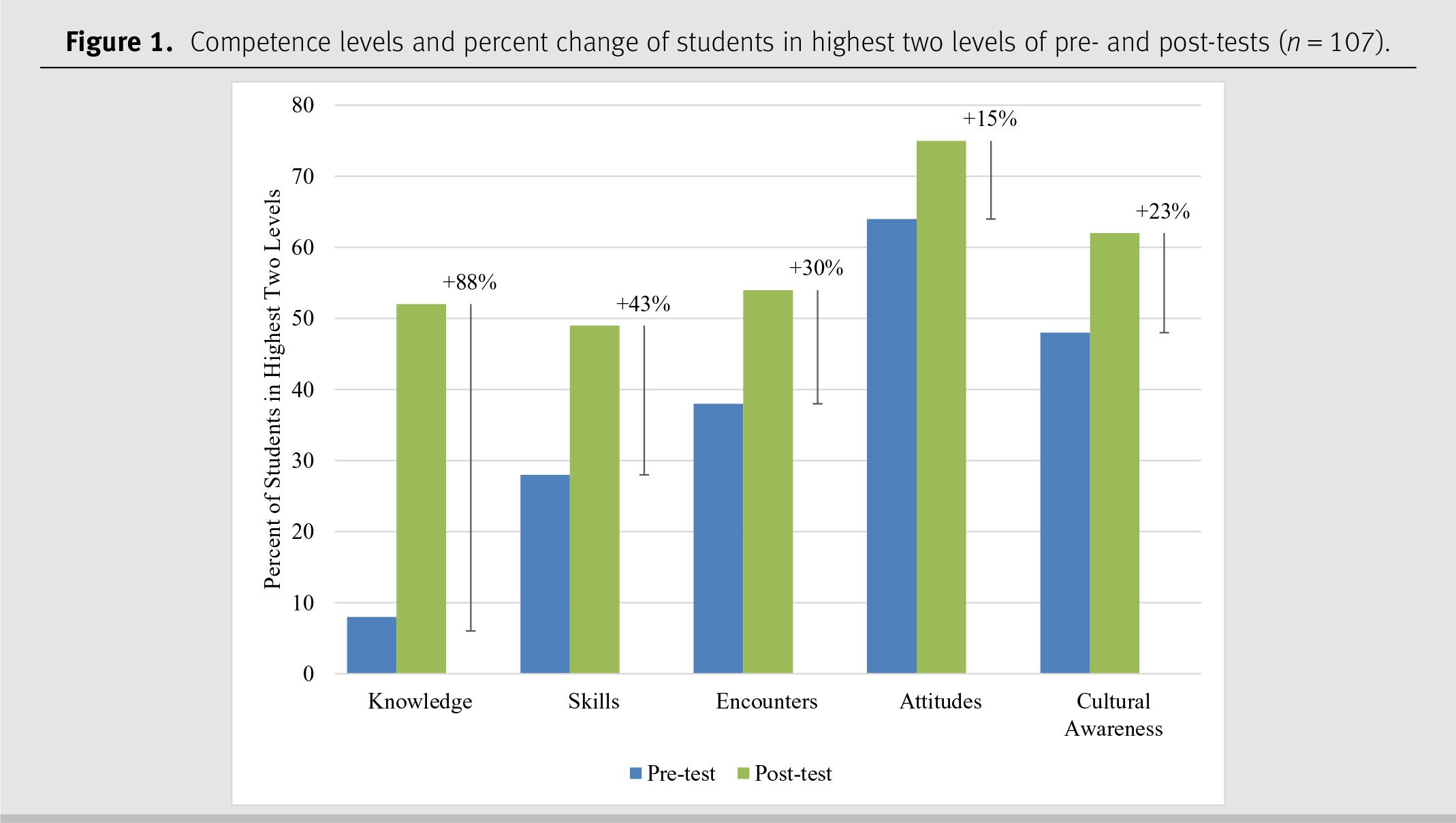

Comparable service-learning projects among nursing students reported by Hsui-Chin et al. (2012) and Kohlbry (2016) reported significantly increased cultural competence scores [

13,

14]. Although only two competence areas (

knowledge and

skills) showed statistically significant increases, our findings indicate a trend towards increasing scores in the other competence areas (

attitudes,

cultural awareness, and

encounters). Dietetic students rated their comfort as high in the post-survey; but this was only slightly higher than the pre-survey (38% vs 54%). However, dietetic internship preceptors reported observing a substantial difference in the student’s comfort and confidence in supporting clients with diverse cultural backgrounds after their participation in Project LINK. Given the cultural homogeneity, dietetic students from Saskatchewan may have limited experience with people from different cultures or ethnicities. One student’s comment exemplified this quite well: ‘

since I grew up on a farm, I feel as though I was somewhat isolated and never directly exposed to different cultural groups that are more commonly situated in urban areas’ (Supplemental Table 1)

1.

The attitudes competence domain shows most students entered Project LINK with positive attitudes towards people of different cultures at 64% in the pre-survey, which increased to 75%. As students’ rated level of comfort in encounters with people of different cultures as relatively low, it is surprising to find that students had comparatively positive attitudes. This could be due to challenges students have in translating attitude into practice or encounters with patients. This highlights the need for additional engagement/encounters to put into practice what is learnt in a classroom setting and that simply providing education on cultural competencies alone is not a sufficient approach. Project LINK provided students with the opportunity to gain experience interacting with people of different cultures, which may have translated into greater comfort and confidence in interacting with people of different cultures when they entered professional practice.

Results indicate Project LINK improved dietetic students’ cultural competence; however, we cannot conclude that students achieved true cultural competence via participation in the project. As proposed by Campinha-Bacote (2002) in their model for cultural competence in healthcare providers, true cultural competence is gained as the areas of overlap between all five constructs of cultural competence increase, because with increasing overlap, the healthcare provider deeply internalizes the constructs of competence [

15]. Consequently, dietetic students who participated have started their journey towards cultural competence but require continual learning in order to become culturally competent.

Project LINK included various activities such as preparing cultural foods, interviewing persons in other cultures, recording experiences in writing, and opportunities to observe home food preparation, handling, and storage in other cultures. A 2020 review of cultural competency training and evaluation methods in dietetics indicated that service learning is an effective method to expand knowledge in diverse communities [

16]. The activities in which students engaged during Project LINK are unique compared to other local service-learning programmes and models, thus demonstrating the unique opportunity provided by Project LINK as a learning tool [

7,

16]. The work by the Project LINK team has continued on a smaller scale, exposing students to cultural competency skills and different health beliefs and practices through the NUTR 310.3 course and other avenues at the University of Saskatchewan.

LIMITATIONS

Cultural competence is subjectively measured and can only be assessed accurately by the individual; thus, generalization of results should be done with caution. Further, the sample of students was small and chosen by convenience, which may reduce generalizability. Additionally, this study design lacks uniformity of the students’ experiences with different families and at different times, which may have impacted the results.